How Media Ownership Shapes the Iran Narrative

- Aslam Abdullah

- Jan 16

- 4 min read

Modern media systems do not operate in a vacuum. They are embedded in political economies shaped by ownership, capital concentration, advertising dependency, and strategic state interests. In much of the global North, major media outlets are structurally intertwined with corporations that benefit from defense contracts, sanctions regimes, energy markets, and geopolitical alignments. This reality does not require a conspiracy theory to explain bias; it requires only an understanding of incentives. When power funds information, information rarely bites the hand that feeds it.

American coverage of Iran is often defended as a neutral presentation of facts. Yet facts are filtered through institutions shaped by ownership, advertising dependence, political access, and alignment with U.S. foreign-policy priorities. To understand why Iran is consistently framed as a singular threat, it is necessary to examine not only what is reported, but how and by whom.

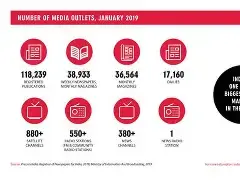

Over the past four decades, U.S. media ownership has consolidated sharply. Comcast owns NBC and MSNBC. The Walt Disney Company controls ABC News. Paramount Global owns CBS News. Warner Bros. Discovery oversees CNN. Major newspapers such as The New York Times and The Washington Post are owned by wealthy families and individuals embedded in corporate America.

These institutions are not monolithic, nor do they operate under direct government command. But they exist within an ecosystem that overlaps with defense contractors, financial institutions, energy firms, and technology companies—sectors with clear stakes in sanctions, arms sales, and Middle East policy. Structural alignment matters even without overt coordination.

Consider sanctions coverage. When the U.S. government imposes sanctions on Iran, headlines and broadcasts frequently adopt official language. On CNN and MSNBC, sanctions are routinely described as “pressure,” “leverage,” or “tools to bring Iran back to negotiations.” The humanitarian impact—shortages of specialized medicines, banking paralysis that disrupts imports, inflation that erodes wages—is often acknowledged only in passing, if at all. By contrast, when adversary states impose economic restrictions, U.S. outlets readily describe the effects as “collective punishment” or “economic warfare.” The policy is similar; the moral framing is not.

The same asymmetry appears in protest coverage. During periods of unrest in Iran, cable networks—including CNN and MSNBC—have devoted wall-to-wall coverage to demonstrations, often relying on looping visuals and social-media footage with limited on-the-ground verification. These stories frequently lead broadcasts for days. By comparison, protests or harsh crackdowns in U.S.-aligned states receive shorter treatment, are framed primarily as “security challenges,” or disappear quickly from the news cycle. The disparity is not about denying repression in Iran; it is about proportionality and consistency.

Print coverage shows similar patterns. The New York Times has produced detailed reporting on Iranian protest movements, often emphasizing state violence and elite corruption. Yet long-form examinations of how sanctions affect Iranian hospitals, universities, or small businesses are comparatively rare and usually framed as secondary consequences rather than central policy effects. The Washington Post, which has run strong investigative pieces on human rights abuses globally, often relies on U.S. and allied intelligence assessments when discussing Iran’s regional role, while applying more skepticism to official claims from adversary states.

Sourcing practices reinforce these frames. Coverage of Iran frequently quotes U.S. officials, Western intelligence analysts, and Washington-based think tanks such as those advocating regime change or “maximum pressure.” Iranian voices outside approved categories—doctors navigating sanctions-related shortages, labor organizers, economists, or independent scholars—appear far less often. Anonymous U.S. officials are routinely quoted with minimal caveats; Iranian officials’ statements are typically prefaced with skepticism.

A clear historical parallel underscores the risk. In the lead-up to the Iraq war, major outlets—including The New York Times and CNN—amplified claims about weapons of mass destruction based on intelligence leaks and official briefings that later proved false. Post-mortems acknowledged failures of skepticism and over-reliance on government sources. Yet in Iran coverage today, similar patterns persist: threat assessments receive prominence, while contradictory evidence is buried or delayed.

Language choices further shape perception. Iran is described as “provoking,” “threatening,” or “destabilizing.” The United States “responds,” “seeks stability,” or “defends interests.” When Iranian actions cause civilian harm, intent is emphasized. When U.S. or allied actions do so, the harm is described as accidental or unintended. These are not neutral choices; they assign legitimacy unevenly.

None of this suggests Iran should be spared criticism. Political repression, limits on press freedom, and harsh responses to dissent warrant rigorous reporting. But selective scrutiny undermines credibility. A media system that demands accountability from adversaries while insulating allied power from comparable examination does not inform the public; it conditions it.

The issue is not individual bias or journalistic bad faith. It is systemic bias rooted in ownership concentration, advertising models, and access journalism. A press embedded in power will struggle to interrogate that power honestly unless compelled by evidence or public demand.

A healthier media culture would widen its lens. It would examine how sanctions affect hospitals, not just regimes. It would ask why decades of pressure have failed to deliver promised outcomes. It would apply the same standards of legality and morality to U.S. actions as to Iranian ones. And it would recognize that credibility depends not on patriotism, but on consistency.

Until then, coverage of Iran will remain less a window into reality than a mirror—reflecting the interests of those who own the platforms and the power that stands behind them.

Comments