Randy Fine Prefers Dogs Over Muslims: Words That Echo Across Centuries

- Aslam Abdullah

- 24 hours ago

- 4 min read

History has an unsettling habit of repeating its metaphors. In the thirteenth-century Central Asia, as Mongol cavalry swept across cities of the Muslim world, chroniclers recorded scenes of conquest that were not merely military but psychological. Persian historians such as ʿAṭā-Malik Juvaynī described how Mongol princes, after subduing towns, sought to break not only walls but dignity. In one oft-recounted episode from the era of the invasions, a Mongol commander—standing amid captives taken from a fallen city—mocked a Muslim family and reportedly asked whether they considered themselves superior to his dog. ¹

The question was not theological. It was not philosophical. It was humiliation as spectacle. The purpose was simple: to erase identity, to strip a people of self-worth before stripping them of sovereignty. Centuries have passed since the thunder of Mongol hooves faded. Yet the language of degradation, when it resurfaces, carries the same cold echo.

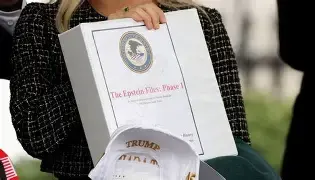

Recently, Representative Randy Fine of Florida ignited national controversy after publicly stating that he would prefer dogs to Muslims. The remark triggered condemnation from Democratic lawmakers and civil rights organizations, while many Republican leaders remained publicly silent. The comment, issued in the heat of contemporary political conflict, did not occur in a vacuum. It joined a broader pattern of inflammatory rhetoric surrounding Muslims, Israel-Palestine debates, and American identity. To understand the gravity of such language, context matters.

Randy Fine is a Jewish Republican congressman representing Florida’s 6th Congressional District. Educated at Harvard, he previously served in the Florida House and Senate. He is widely known for his staunch pro-Israel positions and combative political style, earning the nickname “Hebrew Hammer” among supporters. According to multiple tracking sources, Rep. Randy Fine has received approximately $400,000+ from pro-Israel political action committees such as AIPAC-linked PACs, the Republican Jewish Coalition (RJC), NORPAC, and similar Israel-aligned PACs. This figure reflects reported PAC contributions but can vary slightly depending on reporting cycles and specific PAC breakdowns. He has aligned himself closely with the Trump wing of the Republican Party and has received support from pro-Israel political advocacy networks, including backing associated with AIPAC during his campaigns. He identifies with Conservative Judaism, though his religious life has at times intersected with political controversy.

None of these facts is, in itself, problematic. The United States is a pluralistic republic. Jewish

Americans, Muslim Americans, Christians, Hindus, and atheists—all participate equally in civic life. Nor is firm support for Israel synonymous with hostility toward Muslims; millions of American Muslims coexist with Jewish neighbors, and debates over foreign policy need not devolve into civilizational hostility. But language matters. When an elected official characterizes an entire faith community—over a billion human beings worldwide, and millions of American citizens—as less desirable than an animal, the insult transcends partisanship. It enters the territory of dehumanization.

The United States Constitution guarantees the free exercise of religion. It does not guarantee immunity from criticism; robust debate is essential in a democracy. But there is a distinction between criticizing extremist ideologies and disparaging a faith community as a whole.

The Mongol prince’s alleged taunt was uttered in a world of conquest, where humiliation preceded massacre. The question “Are you better than my dog?” was designed to invert human dignity. It was psychological warfare. Modern America is not thirteenth-century Central Asia. Yet when public officials echo similar metaphors—even rhetorically—the historical resonance is difficult to ignore. Dehumanizing language has always preceded exclusion, marginalization, and violence. In Europe, Jews were once likened to vermin before laws segregated and annihilated them. In Rwanda, Tutsis were called “cockroaches” before the genocide unfolded. Words prepare the ground for action.

A rebuttal to Representative Fine’s statement does not require ideological alignment with his political opponents. It requires moral clarity. First, the generalization is logically unsound. Islam encompasses diverse traditions, cultures, and interpretations spanning continents. American Muslims include physicians, soldiers, educators, entrepreneurs, and public servants. To reduce them to a caricature is intellectually unserious. Second, it contradicts the civic oath every member of Congress takes—to support and defend a constitution that protects religious liberty. The strength of the American experiment lies precisely in its refusal to privilege one faith over another. Third, such rhetoric weakens America’s moral authority abroad. The United States engages diplomatically with Muslim-majority nations across strategic, economic, and humanitarian domains. Words that demean Islam reverberate beyond domestic politics. Fourth, silence in response to dehumanization carries its own weight. When leaders decline to rebuke such language, normalization follows.

It is important to separate legitimate policy debate from religious hostility. One may argue vigorously about Middle East geopolitics, Hamas terrorism, Israeli security, Palestinian suffering, U.S. foreign aid, or national security. These are policy arenas requiring serious discourse. But policy critique loses credibility when framed in contempt for a faith.

The irony is profound: Jewish history itself bears scars of dehumanizing rhetoric. Medieval pogroms, blood libels, and twentieth-century antisemitic propaganda all relied on animal metaphors to strip Jews of humanity. For a Jewish lawmaker—whose community endured centuries of such language—to employ a similar trope against Muslims invites painful reflection. History does not demand perfection. It demands awareness. The Mongol invasions eventually subsided. The cities they shattered rebuilt themselves. The chronicles that recorded humiliation also preserved resilience. Muslim societies recovered, adapted, and continued contributing to world civilization.

Likewise, America’s strength lies not in the absence of offensive speech but in the capacity to confront it with principle. A republic survives when its citizens insist that dignity is indivisible. If one faith can be demeaned today, another can be demeaned tomorrow. The Constitution’s promise protects all—or it protects none.

The Mongol prince’s question, preserved in chronicles, symbolized the arrogance of conquest. It asked captives whether they were less than animals. Modern America must answer that question definitively—not with counter-insult, but with affirmation: no community defined by faith, ethnicity, or heritage is less than human. Not in law. Not in rhetoric. Not in the public square. History echoes. The choice is whether we repeat its cruelty—or learn from it.

¹ The humiliation motif appears in Persian chronicles describing Mongol conquests, including ʿAṭā-Malik Juvaynī, Tārīkh-i Jahāngushāy (History of the World Conqueror), 13th century. Exact wording varies across translations; the episode illustrates conqueror rhetoric rather than a verbatim transcript.

Comments